Why Clean Up the Places No One Lives? Plastic Odyssey’s New Mission with UNESCO

The Cleanup Paradox

Remote, uninhabited beaches are far away, difficult to get to and ecologically sensitive. Visiting these places to conduct cleanups is delicate and expensive. This presents a paradox. On one hand, without dedicated cleanups, plastic will continue to accumulate, threatening wildlife, disrupting biochemical cycles and damaging the inherent beauty of pristine ecosystems. On the other hand, cleanups inevitably create disturbances and require significant time and monetary investment. This creates a strategic challenge: deciding where interventions can deliver the most ecological and awareness raising benefits while minimizing harms and costs. This article explores that challenge, the cleanup paradox, and outlines why remote island interventions can deliver benefits for generations to come.

Paradise Lost, Plastic Found

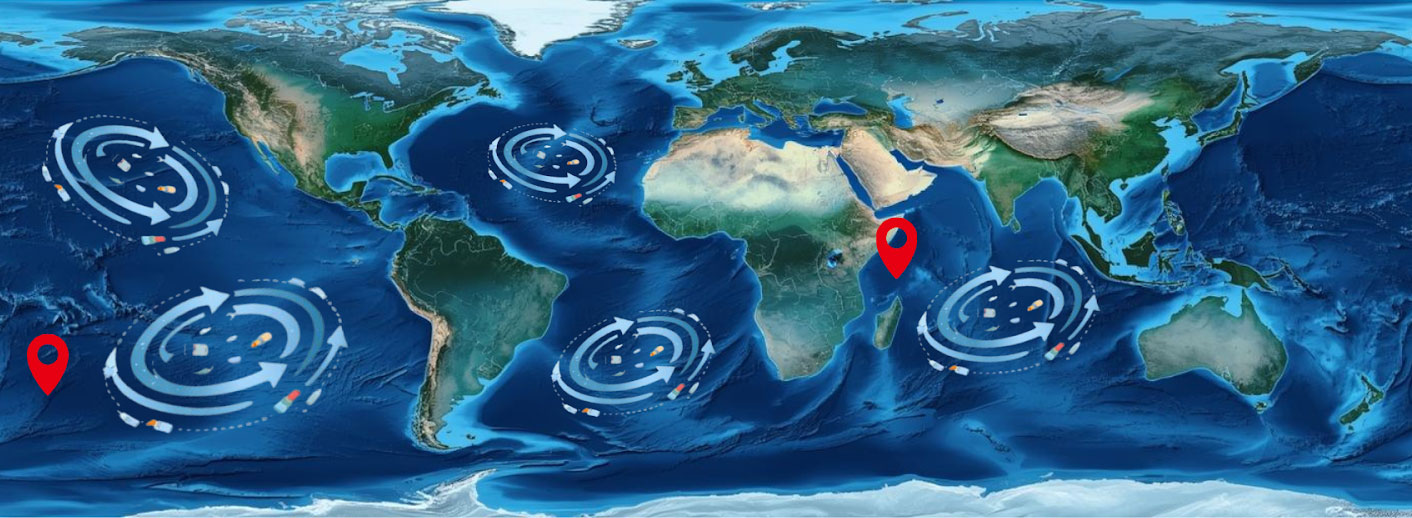

Plastic that enters the environment and eventually the ocean does not disperse evenly. Studies have found much of the plastic in the sinks to the ocean floor while floating plastic can end up trapped in the large, slow moving currents that circumnavigate the world, creating circling ‘gyres’1. Islands that exist in the path of these currents, or gyres, become magnets for waste, which washes up on the shore, potentially from thousands of kilometers away2.

Over time, they collect plastic from many sources and many countries, far removed from the places where it was produced or used. Cleaning these islands, gathering data and telling their stories yields conservation, scientific and social benefits3. This is what Plastic Odyssey is pursuing through its partnership with UNESCO, which aims to restore ecologically significant, polluted islands while advancing scientific monitoring and community-driven solutions.

Why Plastic and Nature Shouldn’t Mix

You may remember the viral video of a sea turtle that had a straw stuck in its nose. A researcher managed to pull out the plastic straw, causing the turtle to sneeze bloodily. It may be one example of plastic harming marine life, but it’s a memorable one. And this type of harm is not an anomaly, a recent study of over 10,000 necropsies (animal autopsies) mapped how much plastic seabirds, marine mammals and sea turtles must ingest to be deadly. Three pieces of rubber (like from balloons) led to 50% mortality in seabirds, while a marine mammal need only to ingest one long piece of fishing line to have the same fate4.

Not only is plastic harmful to animals, it can also kill mangroves if the roots are fully covered in plastics5 and microplastics can disrupt seagrass growth and functioning6. Although research into the effect of plastics on the marine environment is still developing, initial studies suggest the potential for harm, especially when paired with other stressors, like climate change7.

To the naked eye, the sharp neons of anthropogenic waste are clearly out of place on pristine beaches or floating in turquoise waters, but this pollution is harmful beyond the eye-sore. The longer waste is left in the environment, the more likely that an animal will accidentally eat it, mistaking the plastic bag for a jellyfish, or that it will end up settling upon a seagrass meadow or coral reef. Thus, cleanups are the only option to remediate remote areas from waste that continues to wash ashore.

Plastic Does Not Disappear, It Disintegrates

Plastic that reaches these islands does not remain static. Exposure to sunlight, heat, and mechanical abrasion causes larger items to fragment over time. Bottles, crates, fishing gear, and packaging gradually break down into smaller pieces, eventually becoming microplastics that are far more difficult to remove.

This process matters because microplastics interact differently with ecosystems8. They can concentrate toxins, be more easily ingested by wildlife and are more readily incorporated into food webs9. From this perspective, removing macroplastics is a necessary strategy to prevent microplastics and interrupt the trajectory of degradation10. Once plastic degrades beyond a certain point, the tiny pieces are practically unrecoverable as they mix with sand, soil and water. As studies into the true dangers of microplastics develop, it is becoming more clear the dangers of these tiny pollutants and the importance of preventing their proliferation.

Protecting from Plastic for Future Generations

UNESCO is the United Nations agency responsible for identifying and protecting World Heritage sites, which are landmarks or areas of outstanding universal value to humanity that should be preserved for future generations. The sites include the Eiffel Tower and the Great Barrier Reef, which may be protected by tourism organizations, strict entry rules and dedicated management plans, but they also include remote islands, like Henderson Island and Aldabra Atoll.

These islands, deemed worthy of preservation for generations to come due to their geological features and ecological significance, have no defenses against the plastic that washes up on their shores. The endemic birds and endangered species nest among waste, and ingestion or entanglement is a constant threat. Sun and sea further degrade plastics into microplastics. Is leaving these islands untouched really aligned with the goal of preserving them for future generations? Or can interventions, like strategic cleanups, better serve conservation objectives?

Additionally, monitoring plastic in these locations allows for systematic documentation of what arrives, in what quantities, and in what condition11. Waste inventories and material analyses provide valuable insights that can be used to create effective policies and improve management plans.

The Costs of Cleanups

The reality is, however, that remote cleanups are costly12. Access is difficult, transport is resource-intensive, and operations must be carefully designed to avoid ecological harm. Not every site can or should be cleaned, and not every cleanup yields the same benefits.

The key question is not whether cleanups are inherently good or bad, but under what conditions they make sense. Evidence suggests they are most impactful where plastic loads are high and where ecological damage is likely without intervention13. Even then, interventions must be planned to minimize disturbance while maximizing learning and long-term value. This requires site-specific assessment, collaboration with local partners, and a willingness to adapt strategies based on what is encountered on the ground14.

Revisiting the Paradox

There is no simple answer to “why clean up places where nobody goes?” but it is clear that without intervention, plastic will accumulate, marine life will suffer and microplastics will proliferate. In places of outstanding beauty and societal importance, like those designated as World Heritage Sites by UNESCO, cleanups can support the goal of preservation for future generations.

That being said, remote island cleanups will never replace prevention. They cannot address the drivers of plastic pollution, and they do not reduce production at the source. But in a world where plastic pollution is already widespread and persistent, there is an argument for cleaning up what is out there.

Action is costly, but inaction may be costlier. This is why UNESCO and Plastic Odyssey partnered up to conduct cleanups on World Heritage Sites, preserving these remote islands and conserving the species that live upon them for generations to come.

Henderson Island cleanup and monitoring activities. Photo credits: Oliver Löser – Plastic Odyssey

1 Borrelle, S. B., Ringma, J., Law, K. L., Monnahan, C. C., Lebreton, L., McGivern, A., … Jambeck, J. R. (2020). Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution. Science, 369(6510), 1515–1518. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba3656

Jambeck, J. R., Geyer, R., Wilcox, C., Siegler, T. R., Perryman, M., Andrady, A., Narayan, R., & Law, K. L. (2015). Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science, 347(6223), 768–771.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260352

Lebreton, L. C. M., van der Zwet, J., Damsteeg, J. W., Slat, B., Andrady, A., & Reisser, J. (2017).

River plastic emissions to the world’s oceans. Nature Communications, 8, Article 15611.

https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15611

2 Lavers, J. L., & Bond, A. L. (2017). Exceptional and rapid accumulation of anthropogenic debris on one of the world’s most remote and pristine islands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(23), 6052–6057. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1619818114

Ryan, P. G. (2023). Illegal dumping from ships is responsible for most drink bottle litter even far from shipping lanes. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 197, 115751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115751

3 Dijkstra, H., & Tirman, K. (2025). Assessing strategies for remote island beach cleanups: Lessons from the Pacific and Alaska. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 216, 117934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2025.117934

4 Murphy, K. R., Smith, R. C., & Thompson, R. C. (2025). Quantifying the lethal and sublethal effects of plastic ingestion on marine fauna: A global necropsy meta-analysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(5), e2415492122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2415492122

5 Van Bijsterveldt, C. E., Hidalgo-Ruz, V., & Turner, J. P. (2021). Effects of macroplastic on mangrove ecosystems: A review. Science of The Total Environment, 762, 143057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143057

6 Douglas, J., Niner, H., & Garrard, S. (2024). Impacts of marine plastic pollution on seagrass meadows and ecosystem services in Southeast Asia. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 12(12), 2314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12122314

7 Walther, B. A., & Bergmann, M. (2022). Plastic pollution of four understudied marine ecosystems: A review of mangroves, seagrass meadows, the Arctic Ocean and the deep seafloor. Emerging Topics in Life Sciences, 6(4), 371–387. https://doi.org/10.1042/ETLS20220017

8 Jeong, E., Lee, J.-Y., & Redwan, M. (2024).Animal exposure to microplastics and health effects: A review. Emerging Contaminants, 10(4), 100369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emcon.2024.100369

9 Cverenkárová, K., Valachovičová, M., Mackuľak, T., Žemlička, L., & Bírošová, L. (2021).

Microplastics in the food chain. Life, 11(12), 1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11121349

10 Ryan, P. G., & Schofield, A. (2020). Low densities of macroplastic debris in the Pitcairn Islands Marine Reserve. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 157, 111373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111373

11 Dijkstra, H., & Tirman, K. (2025). Assessing strategies for remote island beach cleanups: Lessons from the Pacific and Alaska. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 216, 117934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2025.117934

12 Burt, A. J., et al. (2020). The costs of removing the unsanctioned import of marine plastic litter to small island states. Scientific Reports, 10, Article 14458. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71444-6

13 Falk-Andersson, J., et al. (2023). Cleaning up without messing up: Maximizing the benefits of plastic clean-up technologies through new regulatory approaches. Environmental Science & Technology, 57(36), 13304–13312. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c01885

14 Dijkstra, H., & Tirman, K. (2025). Assessing strategies for remote island beach cleanups: Lessons from the Pacific and Alaska. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 216, 117934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2025.117934