Let’s Bring You To Guinea – Our First Field Action In Conakry

Written by Cédric Stanghellini

Photos: Saran Traore

In February 2022, Jean-Baptiste GRASSIN and Tom BEBIEN traveled to Guinea Conakry to collaborate with a local entrepreneur, Mariam MOHAMED KEITA, and support her in developing her company that recycles plastic waste into paving blocks.

Here is the report on this field trip at the heart of our action against pollution. Read the story of Tom, Jean-Baptiste and Mariam.

Plastic Odyssey’s development of recycling projects in Africa begins with Guinea

After Burkina Faso, this was our team’s second trip to sub-Saharan Africa. Tom and Jean-Baptiste met Mariam in Paris last December during a trip organized by the French Embassy in Guinea.“We were immediately seduced by her project. We first worked on it from a distance to validate its growth potential, then she invited us to discover her business in Guinea.” This trip was an opportunity for Plastic Odyssey to discover Mariam’s know-how and to better understand the ecosystem in which she evolves so that we can act exactly where we are the most relevant for her.

Mariam, A Self-Taught Recycler

Mariam is a true entrepreneur and self-taught recycler.“A few years ago, she started to melt a mixture of different plastic waste, more or less hard, in her garden. She obtained a hot paste to which she added sand to make it more solid. Having created a homogeneous form, it was at this moment that she had the idea of making something out of it: paving stones for the sidewalks and roads of Conakry. The ideal mix of plastic and sand took several tries.” Sand is a resource available everywhere on the spot. And in this context, it is relevant to sequester waste that invades the environment in paving stones useful for the development of the city.

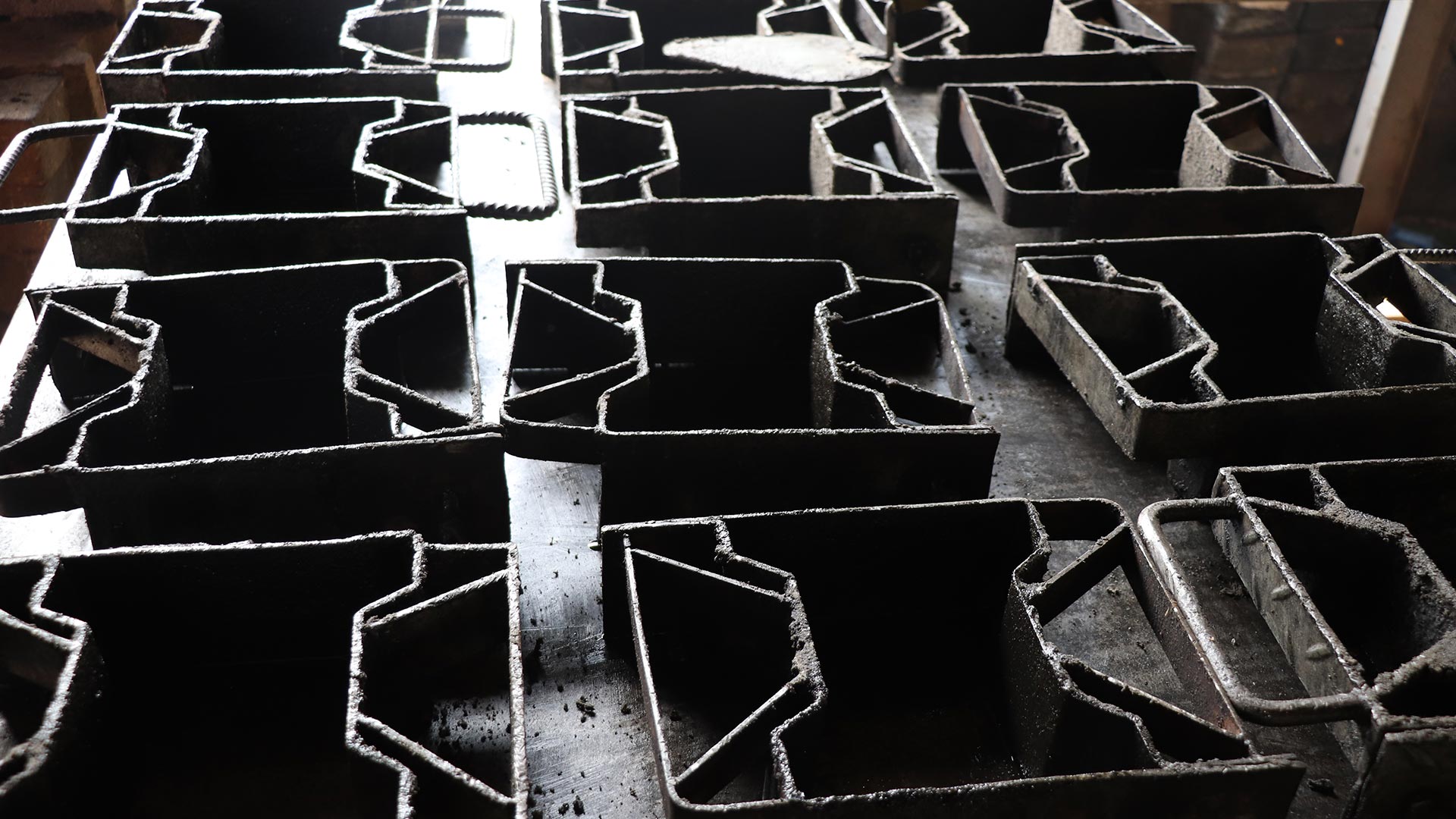

Mariam’s company, Binedou Global Service (BGS), employs nine people, mostly women from her neighborhood. But the means of production have changed little since the first tests. “Under the hangar that houses her business, two small vats are placed over wood fires. The employees pour in plastics, previously washed and crushed by hand, which they stir with large bars. Then comes the sand, carefully measured, incorporated and mixed with shovels. Once the whole is homogeneous, the vats are poured into cast iron molds in the shape of cobblestones.”

The objective of our collaboration with Mariam is to provide the company with technical expertise to increase its production capacity and improve its processes, but also to document and share the technical and economic model that works in our solutions catalog. “It’s a two-way collaboration, a win-win format that brings us a lot in terms of knowledge.”

Waste management in Guinea Conakry

This trip was also an opportunity to understand the functioning of local waste collection and management networks. “One of the first things that strikes you when you arrive in Conakry is the huge amount of plastic waste. On the ground, in the gutters, on the roadside, in the trees. A real silent invasion.” Yet the city does have a garbage collection network managed by ANASP, the Guinean National Agency for Sanitation and Public Health, which entrusts this task to several private companies. “In Conakry, there are large dumpsters where people can deposit their waste. But they all tell us that they find the collection insufficient. The garbage containers quickly overflow. And as no sorting is done, the inhabitants have no choice but to throw everything in a jumble: cardboard, plastic, paper, peelings, metal, wood in the same place. “

Among these wastes, there is one that is emblematic of the West African region: the drinking water sachet. It is a small transparent pouch of about twenty centimeters containing fresh water. Since there is no drinking water network in Conakry, it is distributed by tanker trucks that serve water containers in the neighborhoods. To drink, the most common solution is to buy these small plastic bags of water. And once emptied, the bags are thrown away. “As they are light, they can easily fly everywhere and end up in the sea, because of the lack of waste management” explains Mariam. Because Conakry stretches over a peninsula barely 7 kilometers wide and the city is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean. “The day after the rain, the beaches are littered with waste.”

However, dumpsters can be seen all over the city. There are two sorting destinations in the capital: the official centers run by the authorities and the unofficial ones, called ‘black spots’. Despite their status of non-official locations, on site, things are well organized: “Trucks drop their dumpsters there and soon people waiting in the sun come to search the contents.”

Thanks to our guide, Saran Traoré, a Guinean journalist who speaks Soussou, one of the main languages in Guinea, we were able to talk with workers. In particular with a certain Saïdou Camara, who lives here in the middle of the makeshift houses built nearby. He explains that the waste is sorted on the ground. “Everything that is not useful is burned on the spot. And the ballet of dump trucks never stops. About one every hour.”

How ‘Black Spots’ Work

Who organizes these black spots? Who are the people behind this unofficial sorting system? The questions addressed to the waste-pickers remain without clear answers. “One prefers to remain unclear on this subject” explain Tom and Jean- Baptiste. “Thanks to Saran Traoré’s questions and translations, we understand that the neighborhoods set up near these black spots are organized around chiefs who, in a way, control who can pick up what.” Many Guineans make a living by collecting waste, giving a second life to what is thrown away and earning money from the materials collected. This is not a parallel economy, it is an economic activity.

The city of Conakry is home to many black spots similar to this one. Some are run by men from Guinea’s neighbor, Sierra Leone. As night falls, the activity does not slow down. Equipped with headlamps, these Sierra Leoneans continue to rummage through the dumpsters long after the sun has set. “The working conditions are very difficult and no one wears any equipment, such as gloves to protect themselves from the sharp objects hidden among the plastics.”

Next to the black spots, there are official transit and sorting zones. Managed by ENABEL and ANASP, the trucks deposit their dumpsters in an adapted structure. “We visited one of these official zones and we immediately noticed the difference in terms of equipments for employees and site security. The floor was concreted and all the waste that arrived was sorted.” The will of the Guinean authorities is to increase the number of official sorting centers. “The task is still huge, especially since many people depend on the black spots to support themselves.”

The ‘Miner’, A Huge Open-Air Dump

In Conakry, everyone knows ‘the miner’, the nickname given to the huge dump of Dar Es Salam. A mountain of garbage about ten meters high sitting there in the middle of the houses. “The atmosphere was charged with the smell of decaying garbage. There are many fires lit by the workers, especially to isolate the metal and thus recover it among the ashes. The air is hard to breathe and you get headaches when you stay here for a long time.” says Tom.

As with the black spots, the Dar Es Salam dump site is home to many people, Guineans who sort and recover materials for resale. No fence or wall surrounds the site. The comings and goings of the trucks are supervised by Anasp and an Italian company in charge of weighing the dumpsters. “It is more difficult for us and the journalist to talk to the people here because many prefer to hide their real job from their families. There are also children who glean anything that can be resold, a cloth in front of their mouths to protect themselves from the fumes.” Here again, water bags occupy a predominant place among the waste.

The giant landfill of Dar El Salam is especially known to local residents for its dangerousness. “Every rainy season, whole sections of this mountain of waste collapse, weakened by the weight of the water” explains a site manager who works for ANASP. Workers die as a result. “Some years, houses below are even covered, causing casualties there too.” A week before Tom and Jean-Baptiste’s visit, a 16-year-old girl tragically disappeared under a construction machine that was packing garbage.

But this huge open-air dump should soon be a bad memory for Conakry. The Guinean authorities are planning to build a technical landfill far from the peninsula. A solution that many Guineans we met put into perspective: burying all the waste is not sustainable. On the one hand, it must be reduced. On the other hand, solutions must be found to further revalue those that are already there.

Mariam’s Fight Against Plastic Waste

“I was tired of seeing my neighborhood filled with garbage, everywhere, on the roadsides, on the beaches, in my house carried by the wind. I wanted to do something for Guinea and Guineans.” Mariam Keita is determined to change the image of her city of Conakry where she grew up. Today, her company Binedou Global Service supports nine people, mostly women from her neighborhood. “We produce 200 paving stones per day. But it’s still not enough and for the moment, I only have one client, the Belgian Development Agency, which has ordered 300 square meters of sidewalks. I need more molds, except that they are expensive and some were robbed for the metal.”

Obviously, Mariam has been looking for ways to improve her production, in particular by finding another solution to grind and melt the plastic. She knows that the current process, which is still too small-scale, has its limits and that the fumes released can be toxic for her employees. The only quotation she has received for the moment is from an Indian supplier who proposes a machine at more than 250 000 euros… A cost obviously too high for Mariam, especially since she is not sure that this machine corresponds perfectly to her needs or that she is able to supply it with electricity.

What Next For This Field Project?

The visit to Mariam’s company allowed us to understand her exact needs much more quickly. Today, we can offer her a solution adapted to her constraints and support her in her development.

“Her experience as a field entrepreneur has allowed both the two of us and Plastic Odyssey to learn much more about the simple and effective solutions that can be put in place for recycling. Coming to Conakry allowed us to visually and physically realize the reality of the field, the very concrete impact of plastic pollution, and the essential role of social aspects to be taken into account in these environmental issues.”

At least 1,000 units of paving stones should be produced per day so that Binedou Global Service can have sufficient outlets, the only condition for this solution to recycle plastic waste to be sustainable. This model can also serve as an example to other local actors around the world facing the same situation. Especially since Mariam’s plastic paving stones are less expensive than their concrete equivalent. In Guinea, the potential is immense as there are many investment projects for roads and sidewalks throughout the country.