French Polynesia: ropes woven from coconut fibre

However, this practice has its own harmful consequences for the environment, notably the spread of microplastics in lagoons and the endangerment of marine biodiversity. Fortunately, there is now a great willingness to find alternatives to plastic. Thanks to a collaboration between the Marine Resources Department (DRM) and a local company, a new project was born: Cocorig, ropes made from coconut husk.

The story of Benoît and the Cocorig project

Benoît Parnaudeau, a former sailor with a passion for the sea, settled in Papeete over 10 years ago and launched his sail rope business. Sensitive to the fate of our planet, he has always tried to add a sustainable aspect to his business. He first explored the idea of replacing the stainless steel cables used on sailboats with dyneema alternatives, which are more resistant over time and require fewer resources, although still made of plastic.

Skilled with his hands, he then tried to improve his techniques and innovate, always in the hope of being more ecologically responsible. That’s why he agreed to work with the DRM to find solutions for plastic ropes in the pearling industry.

Adding value to coir fibre

In French Polynesia, coconut growing is of vital importance in this vast territory.

“Every year, over 60 million coconuts fall from the trees, and only 48 million are used for coprahculture (the cultivation of coconut oil). The idea is to be able to recover everything that isn’t used and put it to good use”. Benoît Parnaudeau.

Coconuts are often used for just one of their components, the shell, the husk, the oil and so on. With the Cocorig project, a circular economy is created by recovering every part of this multi-purpose raw material. By using the fibrous part of the coconut husk that envelops and protects the fruit of the coconut palm, it is possible to agglomerate this material to make rope.

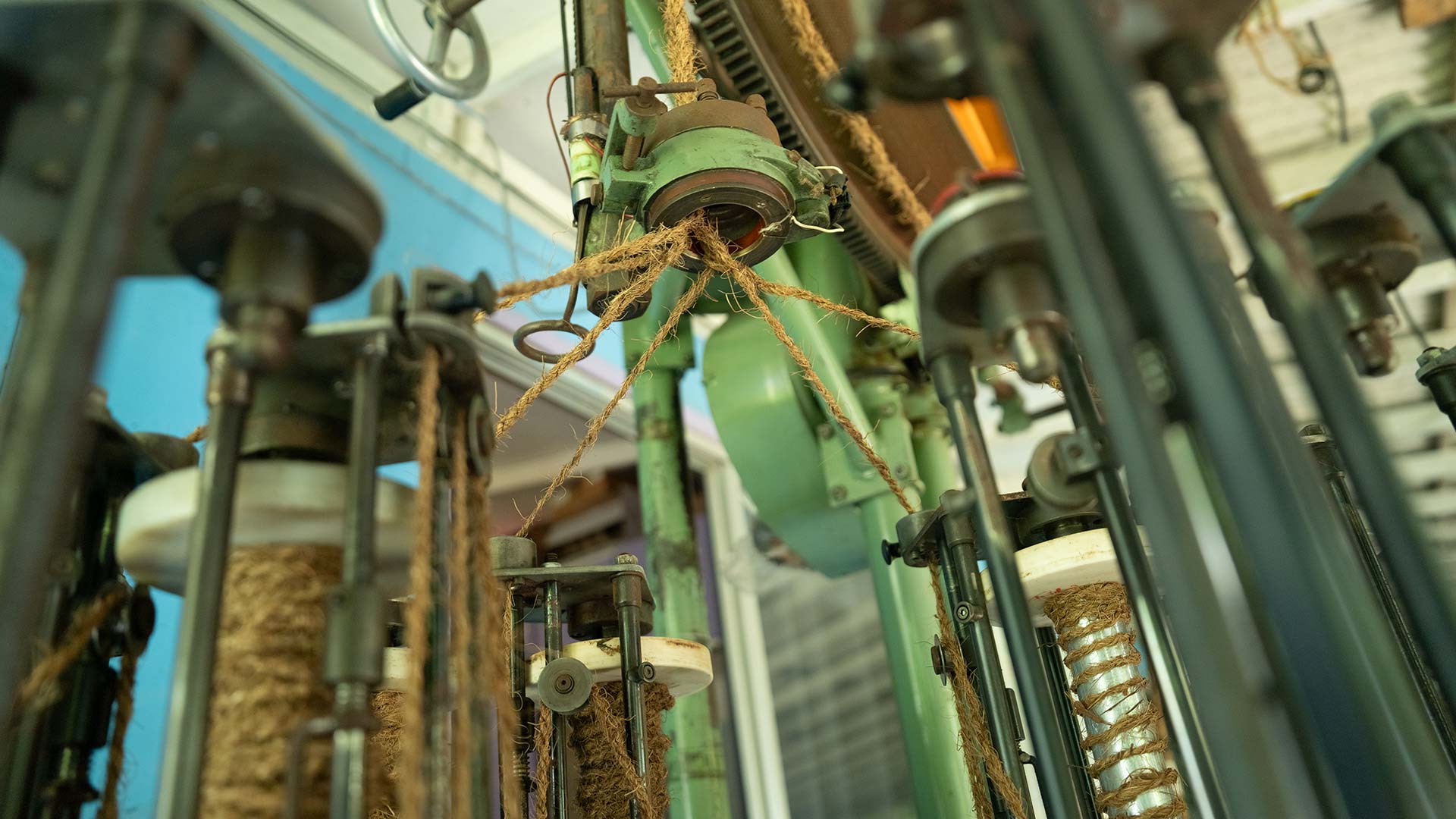

The rope-making process begins on the island of Raiatea, near Tahiti, where coconuts are harvested and processed to extract the coconut fiber. The fibers are then braided for the first time. Once braided, these ropes are sent to Cocorig on the main island of Tahiti. To reinforce the strength of the material, the strands are then interwoven to form the final ropes. Benoît uses a 1978 vintage machine from a French rope factory for this crucial step in the process.

These ropes are currently in the testing phase, as it is still difficult to find a biomaterial that can meet all the criteria of the polypropylene used for pearl farm ropes. So Benoît explores the possibility of using these ropes for other purposes:

“We could very well use these ropes in agriculture. In French Polynesia, there are the equivalent of 140 million meters of rope in agricultural farms, so that would make 140 million ropes manufactured locally in Tahiti, without generating any waste. There are also several outlets for coir fiber, including nets, geotextile fibers, so we’re at the start of a long process.” says Benoît.

Even if there are no ideal solutions for the pearl industry at the moment, the Cocorig project is a very encouraging initiative for the future. It also proves that it can be applied in more than one business sector. Benoît is confident that this technique will evolve over time and become a real solution to plastic pollution.